Understanding Scale in the Solar System

MS-ESS1-3: Analyzing scale properties of objects in the solar system.

When we look at pictures of the solar system in textbooks, they are almost always “lying” to us. They usually show the planets very close together and roughly the same size so they fit on the page. In reality, the solar system is almost entirely empty space, with tiny specks of matter (planets) scattered across billions of kilometers.

To understand this, we must master Scale Models.

1. The Golden Rule of Scale Models

Many students think you can just make the Sun bigger to see it better, but keep the planets close by. This breaks the model. Scale acts like a Zoom Function on a camera.

Imagine the solar system is printed on a rubber sheet. If you stretch the sheet to make the Earth look bigger, the space between the Earth and the Sun stretches too.

Scenario A: The “Basketball” Model

If we scale the Sun down to the size of a Basketball:

- The Earth becomes the size of a peppercorn (tiny!).

- But here is the catch: You cannot place that peppercorn on the desk next to the basketball. To keep the scale accurate, the peppercorn-Earth must be placed roughly 26 meters (85 feet) away.

Scenario B: The “Marble” Model

If we shrink the Sun even more, down to the size of a Marble:

- The Earth becomes a microscopic speck of dust, invisible to the naked eye.

- However, the distance becomes manageable! The Earth-speck is now only about 1 meter away from the Sun.

Key Takeaway: You generally have to choose. Do you want to see the objects (Size Scale)? Or do you want to fit the model in a classroom (Distance Scale)? You rarely get to do both.

(Scroll horizontally inside the black box to see all objects!)

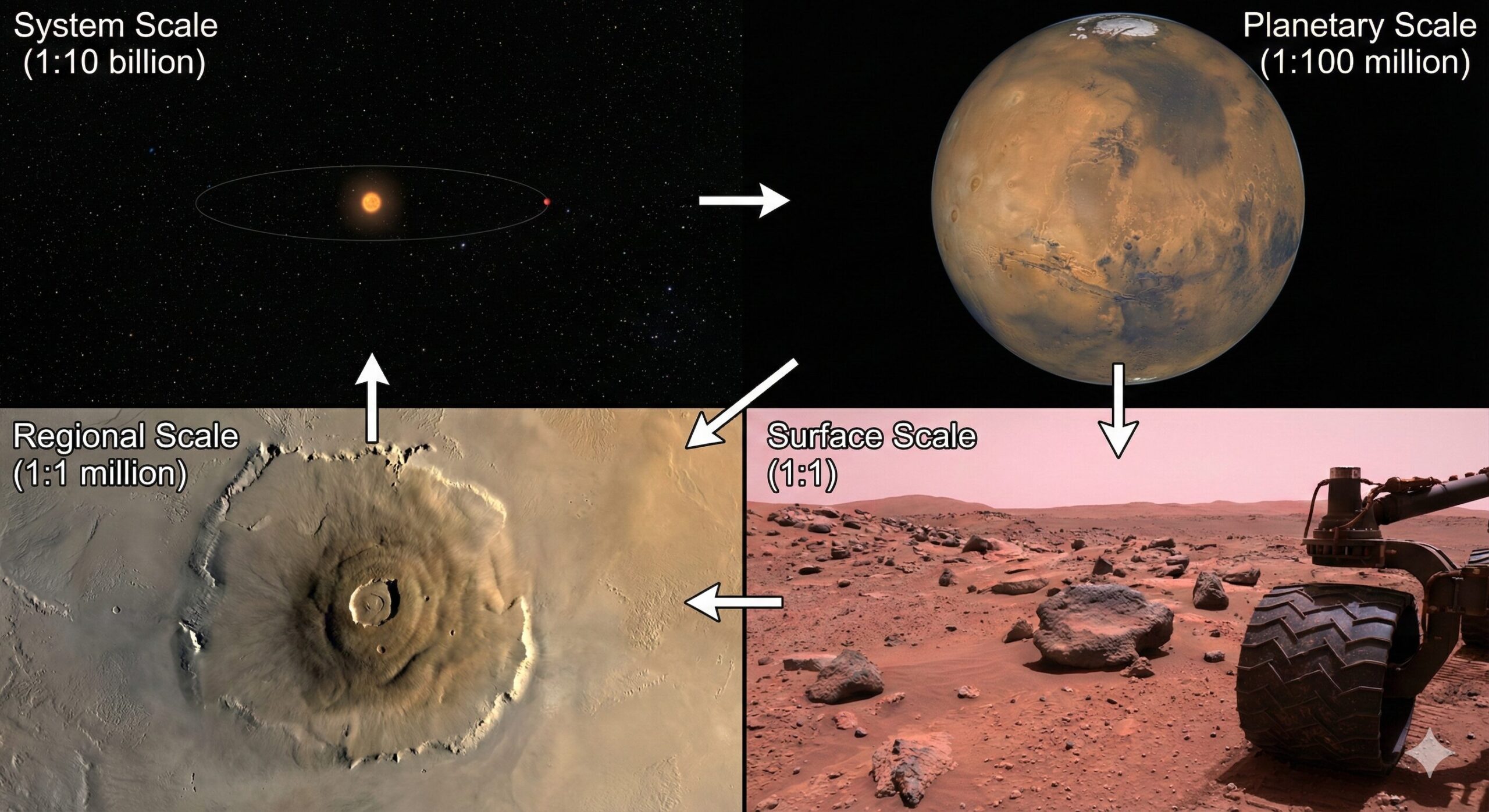

2. The “Resolution Problem”: Features at Different Scales

One of the hardest parts of MS-ESS1-3 is understanding that what you see depends on how zoomed in you are. A feature that is massive to us (like the Grand Canyon) disappears completely when we change our scale to look at the whole planet.

2. Planetary Scale: You see the sphere, colors, and perhaps rings. You cannot see mountains.

3. Regional Scale: You see large craters, continents, or volcanoes.

4. Human Scale: You see rocks, rovers, and footprints.

Example: The Surface of Mars

| If we view Mars at this Scale… | What do we see? | What is invisible? |

|---|---|---|

| System Scale (1 : 10 billion) |

A tiny red dot orbiting the Sun. | Everything. You can’t even tell it is a sphere. |

| Planetary Scale (1 : 100 million) |

A red sphere with white polar ice caps. | We can see colors, but we cannot see valleys or mountains yet. |

| Regional Scale (1 : 1 million) |

Olympus Mons: The largest volcano in the solar system. | We can finally see the volcano, but we cannot see the rocks on it. |

| Surface Scale (1 : 1) |

Rocks, dust, and the Mars Rover. | Now we can’t see the planet anymore, only the ground in front of us! |

📽️ Video: Zooming Out from Earth

Watch how the scale changes from a human on Earth all the way to the edge of the universe.

3. Analyzing the Full System

Our solar system is more than just 8 planets. When creating models, we have to account for the “debris” (asteroids, dwarf planets) and the companions (moons). These objects present extreme challenges for scale models.

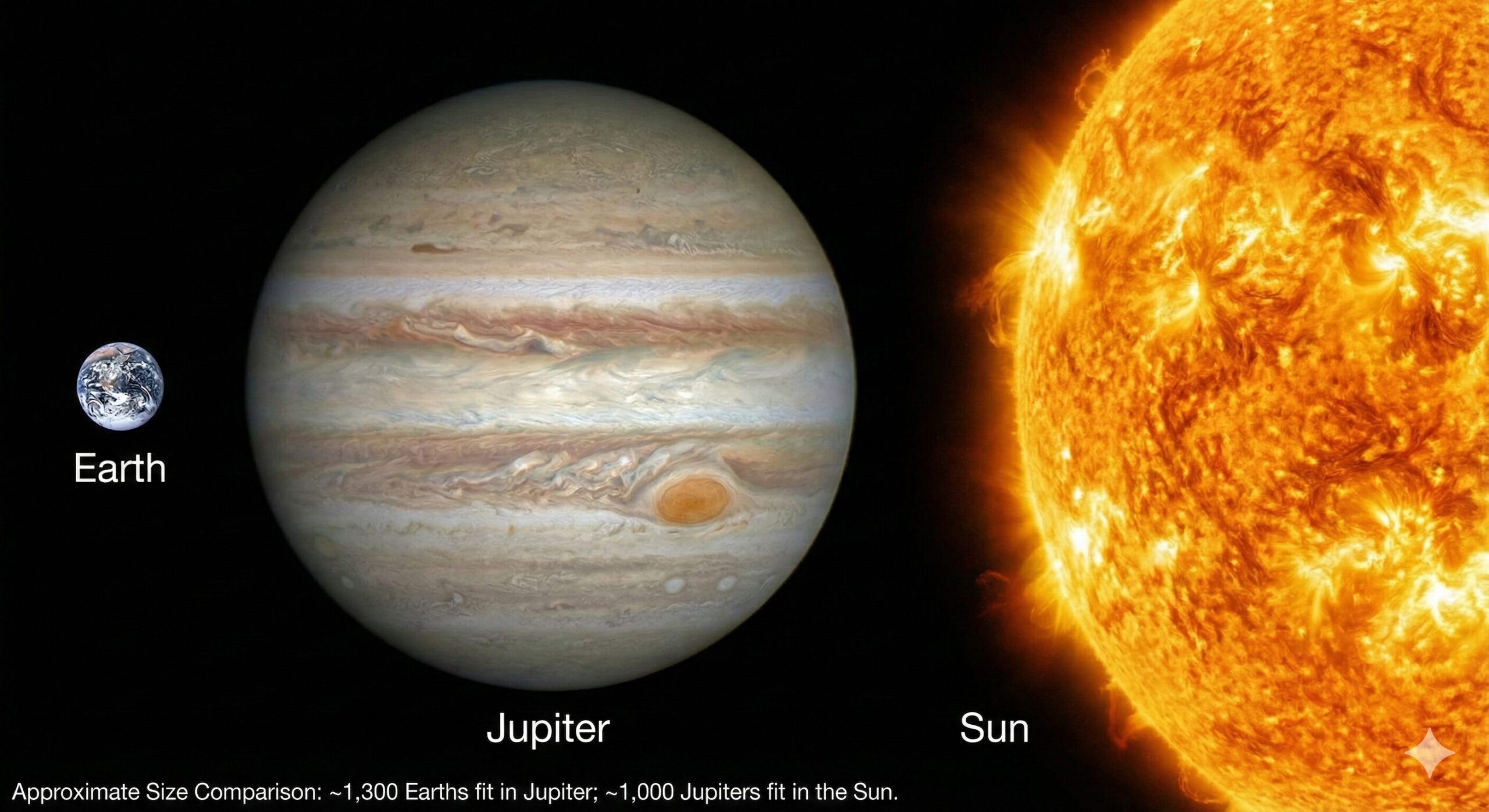

The Giants vs. The Dwarfs

Jupiter is so large that all the other planets could fit inside it. However, compared to the Sun, Jupiter is still small (about 10 Jupiters fit across the Sun’s diameter).

On the other end of the spectrum, we have objects like Ceres (in the asteroid belt) and Enceladus (a moon of Saturn). These are spherical, complex worlds with ice volcanoes and maybe even oceans, but on a Solar System scale model, they are microscopic dust particles.

The Moons

In a distance model, moons are incredibly difficult to show. The distance from Earth to the Moon is 384,400 km. That sounds far, but on a scale where the Sun is a basketball, the Moon is only 7 centimeters away from Earth! From across the room, the Earth and Moon would look like they are touching.

Summary for Your Model Building

As you build your models for class, remember these three rules:

- Consistency: You cannot change the scale for one object without changing it for all of them.

- The Trade-off: If you want to see the craters on Mercury, your model will be too big to fit in the school. If you want to fit the model on a desk, Mercury will be invisible.

- Empty Space: The most accurate feature of any solar system model is the empty space. It makes up 99.99% of the volume.